Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine, and Romania passed the energy openness “test”

The Energy Transparency Index reveals a ‘short-term pain’ paradox – relatively less transparency in the initial phase of more liberalized energy markets and vice versa

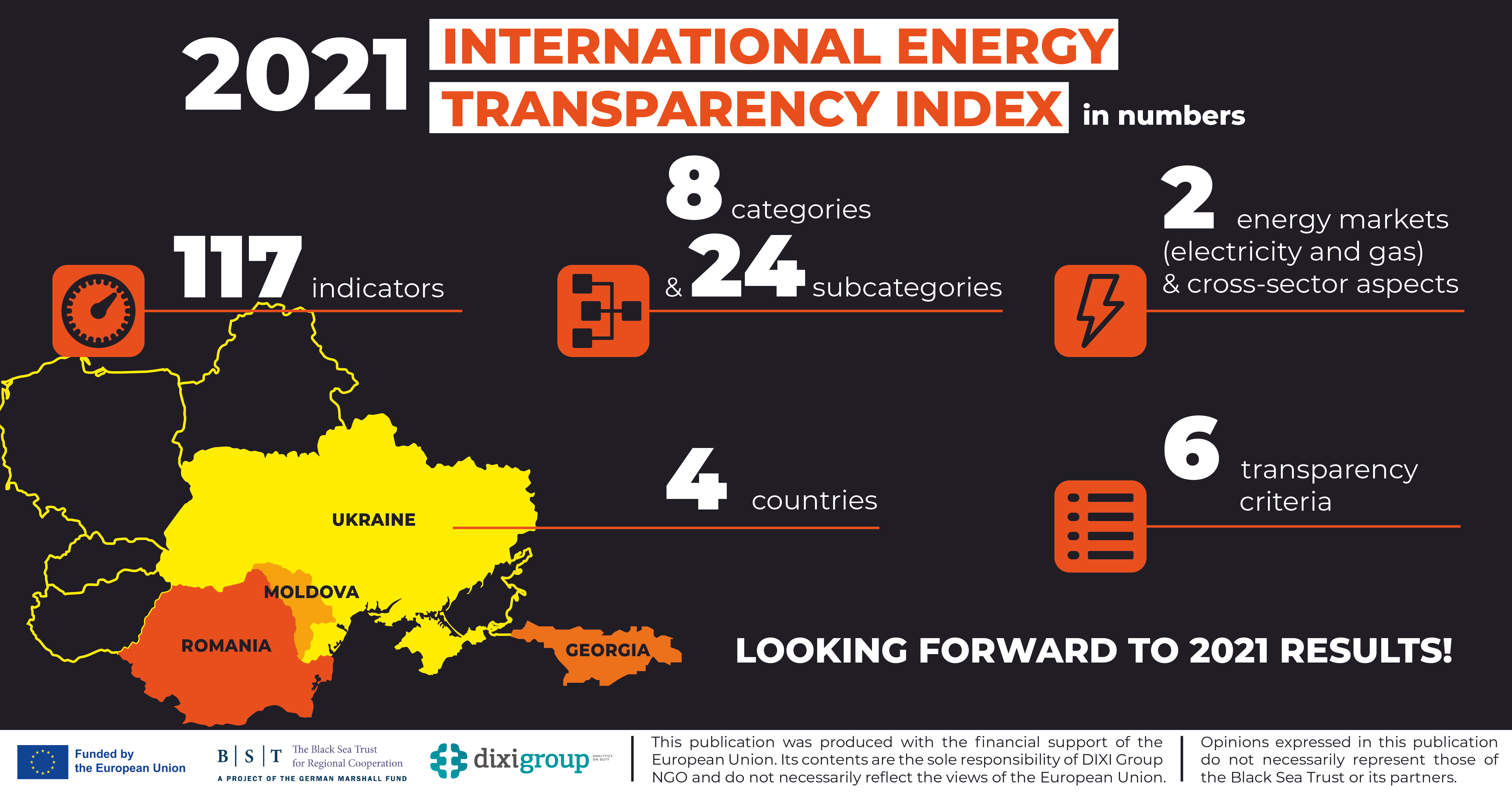

The Energy Transparency Index provides a comprehensive assessment of the energy sector information disclosure in a particular country. The second comparative study in 2021 examines energy transparency in Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine as countries most advanced in European integration among the Eastern Partnership nations and measures the progress compared to the 1st international edition of the Index of 2020. This Index also covers the EU member Romania, considered an appropriate benchmark for the Energy Community countries.

Сontroversial results in general

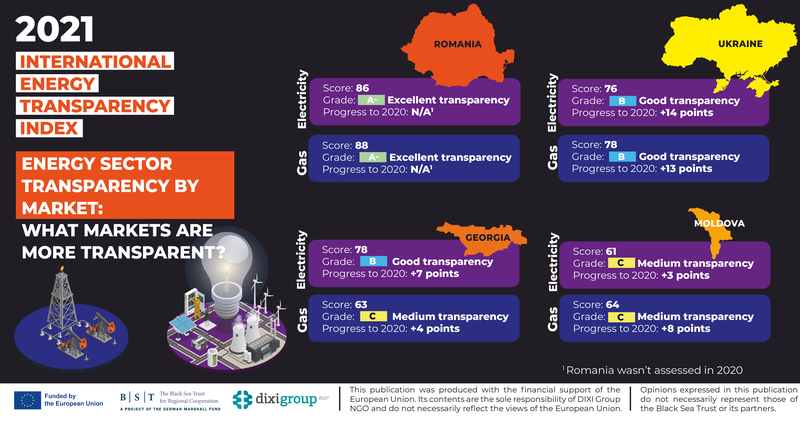

According to the assessment made in 2021, the final scores for Georgia (61, C), Moldova (55, C-), Ukraine (69, C+), and Romania (80, B+) indicate medium or good transparency of their energy sectors and still a significant room for improvement. However, all the countries assessed (except Romania, which was not evaluated in the 2020 Index) demonstrated overall progress within 2-9 points compared to the 2020 assessment, proving that gradual energy reforms according to the EU legislative requirements, particularly of the Third Energy Package, and the best European and global practices, bring greater transparency to the sector.

Transparency strongly depends on the progress toward liberalization of energy markets and the maturity of legislation and regulation. The intensity of internal reforms towards the EU market model defines the applicable rules and requirements on transparency to public authorities and energy companies. Romania, which took the longest path of reforming its energy markets and ensured their performance within the EU single market, legitimately demonstrated the best results compared to the Eastern Partnership countries and can serve as a benchmark. Unlike Georgia and Moldova, Ukraine has transposed most of the related EU requirements into national legislation; still, the question is its due implementation. Moldova is on its way to liberalizing energy markets, while Georgia – the country which joined the Energy Community later – is only rolling out reforms (therefore, some Index’s indicators could not be yet applied and assessed).

Comparing transparency scores of Moldova and Georgia, one could reveal a ‘short-term pain’ paradox – relatively less transparency in the initial phase of more liberalized energy markets and vice versa. This is caused by the introduction of new competitive market mechanisms along with a bunch of strict legislative requirements regarding transparency, which immature markets could fail to meet in the short term. However, in the long run, as the reforms continue and consolidate, the paradox fades and becomes replaced by the gain of greater energy sector transparency which is the Ukrainian case (related to the pre-war status quo).

Having that overall transparency headway, countries demonstrated quite controversial results within the Index’s categories and subcategories, showing a partial decline. These results prove that suspension or delay of reforms, weakened accountability, inconsistent focus, or other distractions may impair transparency in particular areas of the energy sector.

Georgia: need to improve the energy transparency of public spending and decision-making

Georgia demonstrated excellent performance in the publication of energy statistics, but it still failed to disclose information on the independence of transmission and distribution system operators (TSOs and DSOs). Georgia could improve energy markets’ transparency by the publication of exhausting data regarding registers of market participants, market concentration, annual reports on the costs of electricity and gas by consumer bands, and full-fledged market monitoring results. The black boxes remained the disclosure of national plans for electricity and gas security of supply, as well as data on the penetration of meters and smart meters in the sector. It could significantly improve corporate transparency by disclosing management reports and reports on payments to the government by energy companies. In terms of policy, it should ensure the development and publication of the national emission reduction plan (NERP), national energy and climate plan (NECP), and progress reports on the implementation of the national energy strategy and national renewable energy action plan (NREAP). Besides, Georgia should drastically improve the transparency of public spending and decision-making of energy-related public authorities.

Georgia continues energy sector reforms under Energy Community Membership. Despite some progress in recent years, certain setbacks are evident. The establishment of an organized power market had to be moved several times and the full unbundling of transmission system operators in both electricity and gas are still pending. Discussion about Georgia’s future energy mix and development of HPPs face harsh debates and protests from local population, while dependance on imported energy resources, including imports from Russian Federation, increases every year.

“Energy is a complex technological field with a high stake of economic, political and security interests concentrated with a small number of people, – says Murman Margvelashvili, a Georgian energy expert. – Unless properly controlled and regulated, the energy sector can be vulnerable to internal and external actors willing to instill their malign interests through corruption and informal relations at the cost of society and even the security of states. Transparency and data availability in the energy sector is an essential component of accountability, especially in the former Soviet states inheriting energy relations with Russia. Another part should be society’s proper use of this data to control the sector and protect its own interests of free and democratic development”.

Moldova: how to improve data disclosure by stakeholders

Moldova should improve data disclosure by the gas TSO, particularly on available transmission capacity and its allocation, system balancing, etc. Besides, the electricity TSO should publish complete data required by Regulation (EU) 543/2013. Moldova could enhance market transparency by publishing data on switching suppliers and market concentration, complete registers of market participants, and retail markets’ price mark-ups. Also, it should update monitoring reports on supply electricity and gas security. Transparency in consumption could be improved by disclosing smart meters penetration data, commercial offers of electricity suppliers, and related price comparison tools. Government should pay attention to corporate reporting of energy companies as it has ample space for improvement. In terms of policy, it should ensure the development and publication of NERP, NECP, progress reports on the implementation of the national energy strategy, national energy efficiency action plan (NEEAP), and NREAP. Besides, Moldova should considerably improve the transparency of public authorities’ expenditure and the regulatory acts’ impact assessment.

Romania: leading in transparency, ideas for progress

Romania legitimately leads in transparency among countries assessed; however, it still has room for progress. Particularly, TSOs and DSOs in electricity and gas should improve the publication of network development plans along with respective progress reports. Romania should ensure the development and publication of monitoring reports on electricity and gas security of supply and the risk-preparedness plan in electricity. Some improvements could be made in data disclosure on smart meters penetration in gas as well as on energy audit and management. Transparency of policy-making could be significantly enhanced by the publication of progress reports on national energy strategy, NEEAP, NERP, the Low carbon development strategy (LCDS), and nationally determined contribution (NDC) to the Paris Agreement. Besides, Romania should improve the transparency of public spending and decision-making of energy-related public authorities, particularly the regulatory acts’ impact assessment.

A key vulnerability, at least until 2021, was the lack of preparation for emergency situations or potential crises of energy security – Romania historically relied excessively on its own electricity generation and gas production and had not been in the past as much exposed to major disruptions from interruptions of Russian energy supplies, hence a relative lack of focus on such matters until the crisis hit in 2022.

Romania is catching up this year with the preparation of plans for energy security in gas and electricity markets, revisiting the missed deadlines on the implementation of EU regulations of 2017-2019. Generally, various stakeholders are strongly affected by the quality of the legislation, adopted ad hoc and with minimal impact analysis – the current crisis worsened this practice, with decision-makers scrambling to quickly find solutions for the soaring energy prices.

“The authorities, such as the energy regulator, tend to disagree with our score on the network development plans, mentioning that TYNDPs of the gas and electricity TSOs are largely appreciated by peers in ENTSO-E and ENTSO-G. With the massive shifts in EU energy policy such as shift away from fossil fuels and rerouting of gas supplies, network development is key – both for TSOs and DSOs, – says Otilia Nutu, a Romanian energy policy analyst. – However, the 5-year DSOs network development plans are not public, while the projects planned in the TYNDPs of Transelectrica and Transgaz are, almost without exception, delayed by years, with little regulatory intervention to penalize non-implementation. Investors thus have little clarity on whether they can enter the gas or electricity markets in the first place, which is one of the reasons why from 2016 to 2021 there have been virtually zero investments in electricity and gas production in Romania. At the same time, the ad hoc policy-making, the adoption of laws without any serious assessment of their impact on public budgets or energy markets, and proper, inclusive consultations of all stakeholders, is extremely dangerous, particularly during the current crisis when decision-makers feel the pressure to act. Such laws have unintended consequences, which then again require ad hoc corrections. This leads to a vicious circle of ever-changing legislative framework and instability for the business environment in a sector where investors need to plan for many years”.

Ukraine: The Index is a starting point of the situation before the war

Ukraine repeatedly cannot disclose complete data on monthly energy statistics. The TSO in electricity should publish exhaustive data required by Regulation (EU) 543/2013, annual progress reports on the Ten-year network development plan implementation, and produce the risk-preparedness plan. Ukraine could enhance market transparency by publishing complete registers of market participants, retail markets’ price mark-ups, and annual reports on the costs of electricity and gas by consumer bands, which remained black boxes. It should also update monitoring reports of electricity and gas security of supply. Transparency in consumption could be improved by disclosure of gas smart meters penetration data and developing price comparison tools for electricity, similar to gas (Gasoteka). In corporate reporting, Ukraine should focus on the due publication of management reports and reports on payments to the government by energy companies. Transparency of policy-making could be significantly enhanced by the proper publication of progress reports on national policy documents – energy strategy, NEEAP, NERP, LCDS, and NDC, as well as updating of NERP, NEEAP, and NREAP, and development of NECP. Besides, Ukraine should improve the transparency of public spending and decision-making of energy-related public authorities, particularly the full-fledged regulatory acts’ impact assessment.

“Following the russian invasion of Ukraine and the introduction of martial law, the government was forced to close a lot of information regarding the national energy sector, which was publicly available before the war, – says DiXi Group senior analyst and the Index project leader Bohdan Serebrennikov (Ukraine). Due to the national security considerations, we currently observe the trend, which is reverse to transparency, when some data is considered sensitive and becomes closed by the energy regulator, ministries, TSOs, and other entities. Therefore, we consider the results of the 2021 Index as a critical benchmark, which will be applied for assessing the decline in energy sector transparency expected to happen in 2022. International comparison and ranking within the next edition of the Index in 2022 should force the Ukrainian government to thoroughly examine what information is really sensitive and should stay closed and what part could become publicly available again to prevent a significant setback in transparency, worsening Ukraine’s energy markets’ performance.”

This study was made by DiXi Group experts (Ukraine) in cooperation with partners Expert Forum (Romania), World Experience for Georgia (Georgia), WatchDog.MD (Moldova).

This publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union within the framework of “Strengthening transparency of the energy sector in the Black Sea region” project. Opinions expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Black Sea Trust or its partners.