Oil and gas sector of Ukraine: between treason and victory

Ukraine possesses sufficient proved reserves of oil and gas for achieving energy independence in the medium-term perspective. According to the data published in the OPEC annual report 2016, such reserves in Ukraine amounted to 395 million barrels or 54 million tons of crude oil (table 3.1), and 952 billion cubic metres of gas (table 9.1). However, currently that potential hasn’t been used in full.

For example, according to the statistics of the Ministry of Energy and Coal Industry, domestic production of natural gas was almost 20 billion cubic metres and covered only 62% of consumption, with the rest of gas volumes needed imported into the country. The crisis showing acute fluctuations of automobile gas prices back in summer 2017 was a bright example of the market’s overdependence on the energy carriers’ imports.

It is not surprising at all that significant increase in domestic energy production, especially, insofar as it concerns natural gas, is among the Government’s priorities. However, in order to increase the level of hydrocarbons’ production up to the volumes of domestic consumption, respective investments in the industry are needed, and the size of the capital raised is, in its turn, directly dependable on the business climate. It is quite clear that contradictory legislation, high rate of corruption, inefficient judiciary would entirely discourage any investment in Ukraine. At the same time, extraction industries are full of yet another broad range of threats to sustainable development, which are intrinsic to them. Those include inadequacy of land law, confused and over-regulated authorisation system, unstable rent and tax rules, and under-regulated issues relating to minimisation of damage to environment and taking into account interests of local communities, which raises significant corruption risks.

Nonetheless, one should take a bigger picture of the quality of management of extraction industries: more transparent regulatory procedures, incentivising taxation policy, clear and mutually beneficial rules of co-operation with the local communities, consistent and responsible use of the rent revenues by the state — all those aspects possess a huge potential for a positive impact on the society. Norway is a classic example of a reasonable and forward-looking policy as to such management resulting in the sovereign wealth fund approaching 1 trillion US dollars, and its standard of living is considered one of the best in the world.

Unfortunately, such a situation is rather an exception, for the majority of the countries rich in natural resources show quite different features. They have a high rate of corruption, a huge share of shadow economy, and “chosen” extraction companies and officials associated with them may enrich themselves, while population’s living standards remain low. It is clear that such situation does not foster improvements of the business climate in the industry, nor does it lead to real enrichment of the country as a result.

The brightest example of such situation is Venezuela whose proved oil reserves are over 300 billion barrels or 41 billion tons of crude oil (it is 740 times more than in Ukraine). At the same time, according to the Corruption Perceptions Index, that country rated 166th among 176 countries in 2016, and now is drawing fast near the final collapse of state institutions.

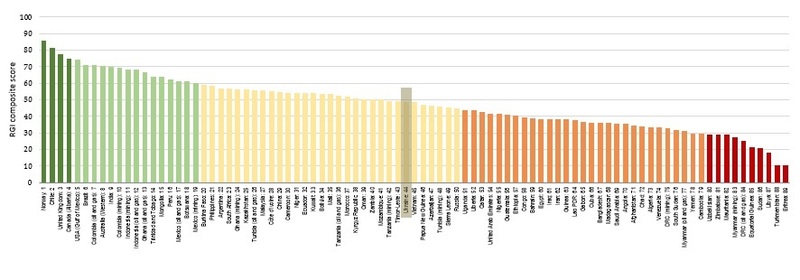

With the view to the more detail analysis and identification of the problematic aspects hindering efficient resource management, the experts of the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) have developed their own comprehensive evaluation methodology which has already been used for two years for preparation of the global Resource Governance Index. It comprises three components — value realisation, revenue management and enabling environment, which, in their turn, taken together, consist of 14 subcomponents. For more details of the methodology click here.

Source: Resource Governance Index(RGI) 2017

Resource Governance Index 2017, account taken of quire mediocre results it showed for the oil and gas sector of Ukraine, is to be considered not only as one more rating for Ukraine but also as a tool that the authorities could use for clear diagnostics of those bottlenecks in the oil and gas extraction industry and employing comprehensive approaches in its reform.

Generally, in 2017, the Index covered 81 countries, with some of them evaluated separately both in respect of their oil and gas sectors and mining sectors, so there are 89 evaluations in total. Ukraine had got on that list for the first time and was one of the three European countries (apart from Norway and UK) under evaluation. Nonetheless, if Norway and UK fell into a not so numerous group of countries which “do well”, Ukraine found itself in a “weak” group, with such neighbours as Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Russia etc. Ukraine has scored only 49 points out of maximum 100, which made it possible for our country to place 44th in the rating.

Source:RGI Ukraine

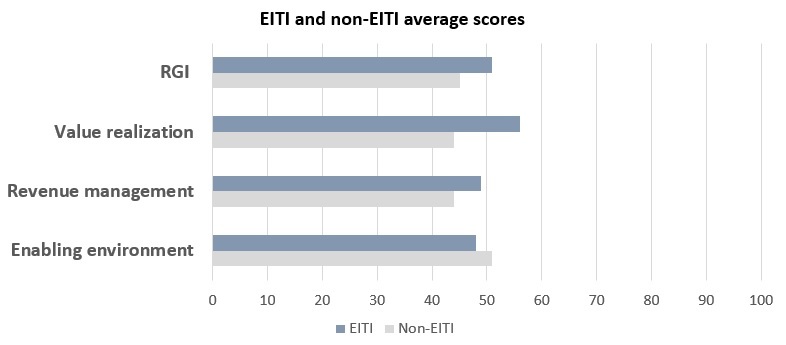

There is an interesting fact of correlation between the Resource Governance Index and the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). Taking into account that the Initiative provides for ensuring transparency in the country’s natural resource management and disclosure of public revenues from the extraction industries, it is reasonable to expect that the more open the country will be, the higher rating it is to receive in the Resource Governance Index, and the facts support that assumption. Therefore, the diagram shows that EITI member countries, on average, show better results in the Index than those that stay outside the Initiative.

Source:Presentation of RGI in Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (7th of July)

In the light of the aforesaid, further support of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative becomes even more necessary. By now, Ukraine has published two reports in the framework of the Initiative but the country still lacks legal framework for the mandatory implementation of all standards reflecting the world’s best practices. With the view of that, this year saw an attempt to adopt a draft law on the transparency in extraction industries but as a result of the political games in the Parliament the vote failed. The draft law has now been re-registered with the Parliament and is pending repeated vote in autumn.

Besides, other draft acts may be found pending in the Parliament (and in the Government’s work programmes), and they are capable of substantially improving natural resource management in Ukraine. In particular, it is about the draft law No. 4646-д (implementation of up-to-date bookkeeping and financial accounting standards) and deregulation draft law No. 3096-д, as well as about proper implementation of the already adopted laws No. 1793 (on partial rent decentralisation) and No. 2059 (on environmental impact assessment).

So, the scrutiny of the effective work of the people’s deputies this autumn may have tangible results in improving natural resource management. At the same time, there is much to be done by the state and NGOs as regards rule-making a regulatory work in years to come.

Generally, according to the Index, Ukraine is rated pretty low, and in order to improve, a more comprehensive approach is to be taken. Therefore, even adoption of some laws will not remedy the situation. Improvement may be only possible in case the Government and the Parliament, as well as local self-governing authorities, extraction companies themselves and local communities are fully committed to work jointly on the implementation of such decisions in the industry. The outcome of that work will show what country Ukraine will look more like after ten years — Norway or Venezuela.

Andrii Bilous, Mariia Melnyk