Gazprom’s storage facilities are “powder kegs” of the European gas market

EU should impose stricter rules on the use of underground gas storage facilities against unfair market players

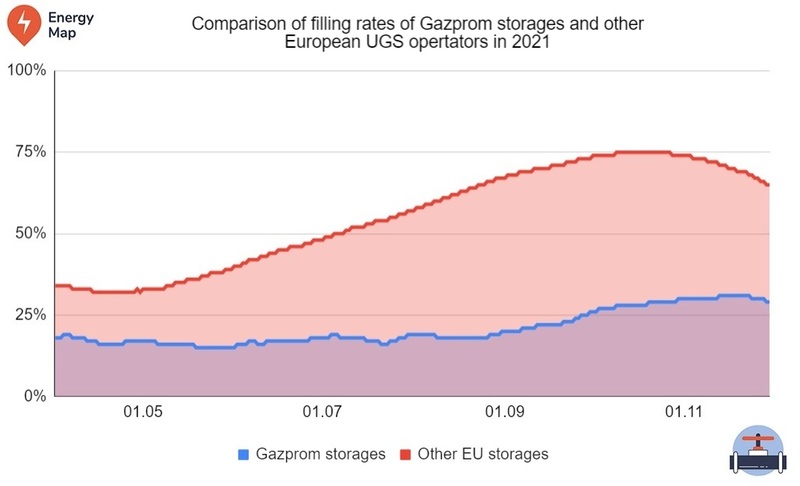

Gazprom has largely contributed to current crisis in the EU gas market. One of the tools for deepening thereof became the European underground gas storage (UGS) facilities, which before the war were controlled by the russian monopolist. They became a kind of “powder kegs”, to which little attention was paid while UGS facilities were properly filled. However, in the 2021 injection season, “powder kegs detonated”, as Gazprom filled its UGS facilities by only 31%, while the European average was 75%. Thus, the russian gas monopolist has once again confirmed its unreliability as a supplier.

How Gazprom’s storage facilities operated in Europe

Before the war, Gazprom controlled a number of underground gas storage facilities in Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, the Czech Republic and Serbia. The volume of these facilities is estimated at 12.3 billion cubic meters (these are storage facilities in which Gazprom or its subsidiaries have a stake), another 2.5 billion cubic meters are reserved in other storage facilities.

Energy Map’s data on the operation of the European UGS facilities makes it possible to compare how the UGS facilities of Gazprom and other European gas storage facilities were filled in different years. Consider relevant dynamics in the “crisis” 2021 year.

Last injection season, Gazprom’s highest storage filling rate was only 31%, while for other EU’s UGS the filling rate reached 75%. At that time, the russians justified themselves by saying that their priority was to fill their own storage facilities in russia. But even after October 2021, when stocks in russian UGS facilities reached a “record” 72.6 billion cubic meters and volodymyr putin promised to increase supplies to Gazprom’s European storage facilities, but the expected filling did not happen.

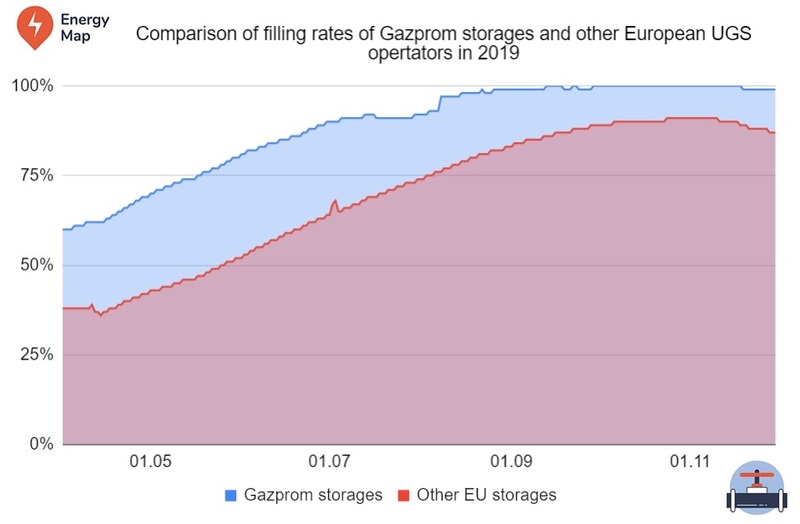

Contrasting with these indicators are similar data of 2019.

Three years ago, the situation was reversed: Gazprom’s storage facilities were in the forefront of injection, accumulating gas faster than the EU average. This was due to the fact that Gazprom had a direct interest in filling its European UGS facilities, as Nord Stream-2 was still under construction, and the transit contract with Naftogaz expired at the end of 2019.

In general, Gazprom’s storage facilities were regularly filled in 2017, 2018 and 2020 as well, and therefore the issue of UGS belonging to the russian monopolist and relevant risks were not made public. However, these risks existed, and in 2021 they were implemented: Gazprom did not fill its UGS facilities in EU. Moreover, the sabotage coincided by time with a record rise in gas prices, just when the European customers became interested in maximum stocks for the winter.

READ ALSO: On the eve of the gas crisis, Europe accelerated rates of filling UGS

Such actions are a bad move for a “reliable supplier”, but for a geopolitical player it is an additional opportunity to put pressure on important issues, such as accelerated certification of Nord Stream-2. Thus, 12 billion cubic meters are unlikely to “make the weather” in the European market of about 400 billion cubic meters, but combined with the existing market power of Gazprom in the form of 40% of the European imports, these assets become additional levers of influence on the market.

Legal safeguards did not prevent manipulations

The European Union has well-developed regulation of the natural gas market, but in the event of Gazprom’s European storage facilities, safeguards against monopolism and non-competitive behavior have failed.

One of the safeguards is unbundling, i.e. functional and legal separation of competitive activities in the gas market (supply/production) from those that are non-competitive in nature (gas transportation and distribution). The form of separation can be different: from simple unbundling of accounting by different activities of a vertically integrated company to radical ownership unbundling, according to which a legal entity that owns and operates distribution or main networks must be completely independent of the enterprise engaged in gas production/supply.

Gas Directive 73/2009/EU provides for a “softer” form of unbundling for gas storage activities – legal, where the UGS operator is a separate legal entity, however remains part of a vertically integrated undertaking. It leaves room for abuse, therefore the Directive provides for radical ownership unbundling for GTS operators. In the light of recent events, the transition to such a model of unbundling seems appropriate for operators of storage facilities as well.

The second safeguard is the principle of free third party access (TPA), i.e. legally assigned right of independent entities to have access to infrastructure owned by another entity on a non-discriminatory basis. This principle also applies to UGS and can be embodied in the form of a regulated or negotiated TPA. The regulated model envisages that the energy regulator “centrally” determines non-discriminatory and transparent conditions of access to storage facilities, in particular by establishing an appropriate tariff policy. Under the negotiated TPA, the provision of access to capacities and conditions thereof are the result of negotiations and arrangements between operator of storage facilities and its users, while energy regulators only create the conditions to reach such arrangements.

According to data of the European Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER), in Austria and Germany, where Gazprom’s largest storage facilities are located, there is the TPA negotiation model that gives an operator of storage facility more freedom in determining the conditions under which it provides access to its own capacities. The Gas Directive stipulates that appropriate negotiations between an operator and users of storage facilities must be conducted in good faith. However, good faith of Gazprom’s former “subsidiary” astora (the operator of a number of storage facilities in Austria and Germany) may raise questions given its connection to Gazprom. Of course, no direct evidence of astora’s misconduct in the distribution of own capacities has been provided, but it is worth noting a number of features of capacity distribution by this company that could pose risks to TPA.

Firstly, most of the capacity of astora’s storage facilities was distributed at the request of users (binding request) according to the principle “first come – first served”. That is, an entity which is the first to file a request for capacity reservation will be provided with them first. Moreover, under the general conditions of access the time and capacity that the user can rely on in the request are in no way limited. Part of the capacity was offered at the automated auctions, but it was small amount: for example, at five auctions for distribution of Haidach storage capacities for 2021-2022, the allocated amount of gas storage ranged within 10-40 GWh (1-3 million cubic meters) (example). Since almost all astora’s UGS capacities have already been reserved for several years ahead, it is likely that these capacities were provided at the request, a procedure that is less transparent than auctions. Given the connection of astora with Gazprom, this could carry risks for TPA implementation by third parties.

Secondly, astora has no effective safeguards against unfair reservation of its capacities. This phenomenon is called hoarding – when user of storage facility reserves significant UGS capacities, but then simply does not use them, while preventing the use by other players in the market. The conditions of access to astora’s storage facilities contain hoarding safeguards, but they look very weak: in order for an operator to be able to deprive an unfair user of the reserved capacities, the latter must not use them for a whole year.

What to do in current situation

Given the current realities, it is primarily advisable to make changes to the Gas Directive that would provide for ownership unbundling for UGS operators. At the same time, in the future certification of UGS operators, which is provided for by relevant EU Regulation, the energy regulators of the EU countries and the European Commission should pay attention to the links between UGS operators and gas suppliers for their compliance with security objectives for natural gas supply. In parallel, the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Competition is to investigate actions of Gazprom and its subsidiaries in the field of gas storage. The investigation should be part of a broader study of Gazprom’s behavior in the gas market.

Also for this heating season, the European UGS users may consider using the Ukrainian storage facilities as an alternative to using Gazprom’s UGS in the EU, as even though the greatest assets have been transferred into temporary use of the German government, filling them may involve legal risks. The UGS capacities are formally distributed for several years ahead. In the future, the German and Austrian governments should consider an option of nationalization or forced sales of relevant UGS facilities to eliminate any risks of non-filling in the future. This is important because, for example, the operator of a part of the Haidach storage facility is GSA, which still remains a subsidiary of Gazprom.

Andrii Ursta, DiXi Group analyst